ESTea #21 11/11/21

The Government claim that the UK has reduced its emissions footprint by 42% since 1990, which is a commendable feat. That has been achieved in part by offshoring manufacturing and outsourcing many emissions to countries such as China that produce the goods we consume. If we factor in those emissions, the UK emissions reduction is possibly as little as 10% to 15%. Ahead of COP26, what steps will the Minister take to include the full scope of our emissions in the accounting, including those arising from UK consumption, supply chains, and international aviation and shipping?

Sarah Olney M.P.

Sarah Olney is not the only person criticising the UK government for ‘offshoring’ emissions from the period 1990 to 2020. Offshoring in this context means that either emissions that used to occur in the UK, now occur in other countries, or that new emissions have been created in other countries that properly should ‘belong’ to the UK.

This view has been expressed by protestors, activists and, occasionally, by fund managers over the past weeks of COP26.

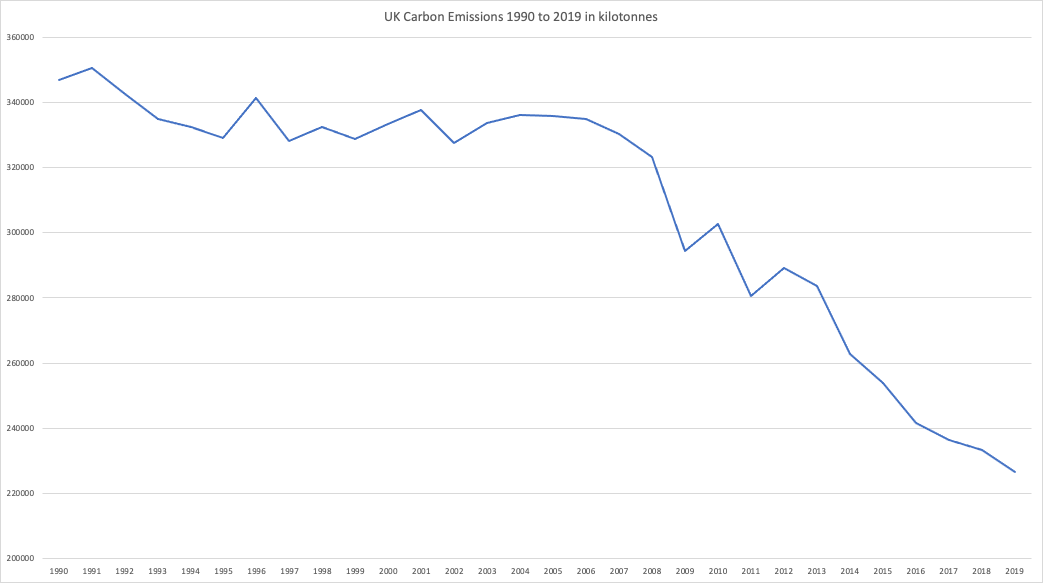

This objection typically arises as is a response when it’s mentioned that the UK has decarbonised extremely quickly – and more quickly than other G20 countries. In the period from 1990-2019, raw emissions have decreased by 35% (unsure where 42% came from) despite rising population, economic growth and consumption.

That 35% reduction means around 32000 fewer kilotonnes of carbon emissions each year in the UK.

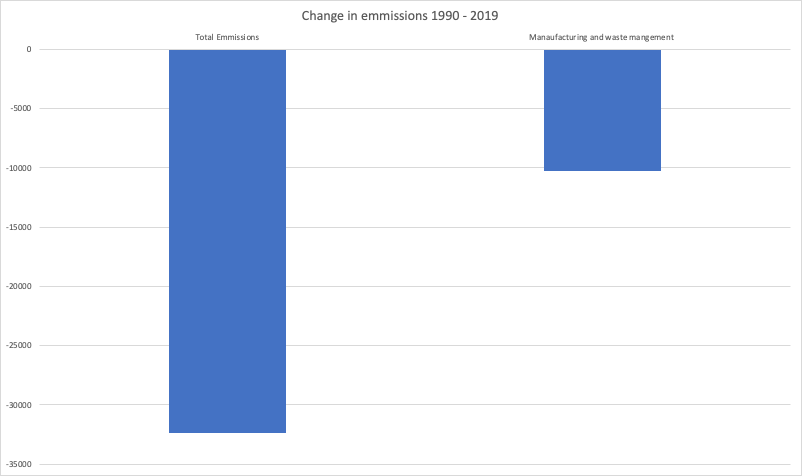

Where have the principle reductions from? If it was the case that offshoring manufacturing has driven these reductions then we’d see substantial decreases in the carbon emitted by sectors like waste management, manufacturing and energy production. However, this is not the case and instead, we see only a modest fall in these sectors.

This change in emissions accounts for all oil and gas production, all manufacturing and all waste management. Not only the elements which could be offshored. Even if all energy production, all manufacturing and all waste management were offshored – it wouldn’t account for more than a fifth of the UK’s decarbonisation.

You could argue that there’s been a hidden increase in consumption in the UK, resulting in an entirely overseas growth in carbon emissions but the problem is that manufacturing doesn’t account for much of the carbon footprint of any country. The principal contributors are almost always electricity production, transportation and home heating – items that simply cannot be offshored.

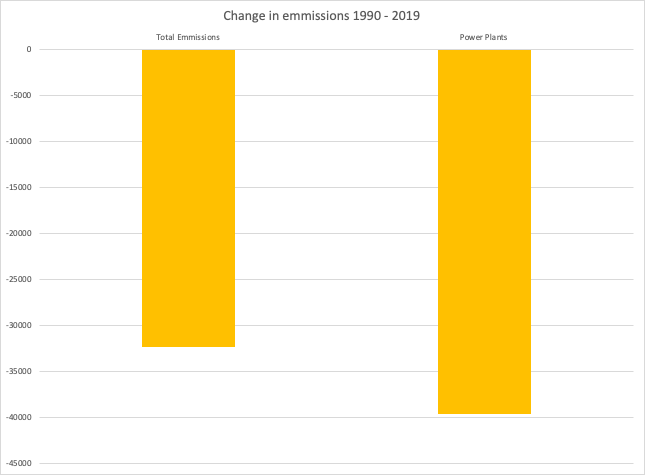

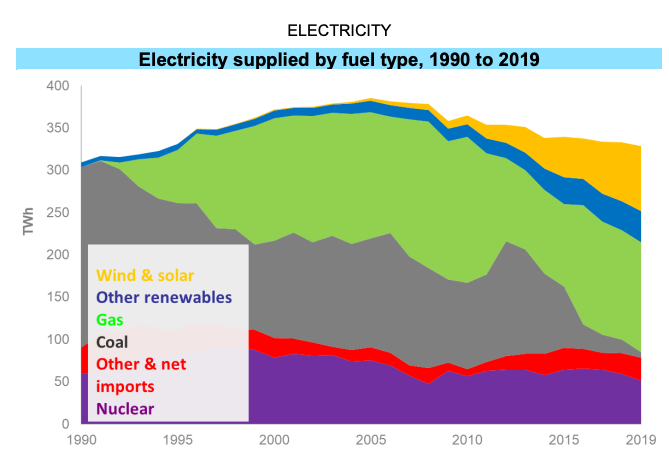

So where does this huge change come from? The answer is very simple: electricity generation.

The United Kingdom decarbonised the National Grid at an unprecedented rate – while other sectors ended up producing even more carbon.

Coal has been almost entirely eliminated from the grid and replaced with a mix of natural gas and renewable energy (principally wind power). Since energy produced with natural gas produces approximately half as much carbon dioxide per kilowatt, this still makes a considerable contribution to the decarbonisation of the grid, and of the country.

Why should you care about this?

It seems that the UK really is leading the way for developed economies’ and their decarbonisation efforts. If COP26 (or any future COP) is a success then other rich countries will be looking for ways to meet their commitments and reduce their carbon emissions. Smart countries will look for successful examples and the United Kingdom should be the first place they look.

Those people muddying the water about UK decarbonisation will only confuse and distract those other counties as they look to copy the UK’s enviable record.

There are investors in the market looking to predict how countries will look to decarbonise over the coming years and capitalise on those opportunities. The model set by the United Kingdom is sufficiently successful that other countries quite probably will look to copy their mix of government investment, pseudo-markets and a specific focus on decarbonising electricity generation.

This looks to be a sign that coal internationally will be under enormous pressure from governments and regulators. At the same time, gas and wind power could receive the boost they have already enjoyed in the United Kingdom.